The Cape of Good Hope was a welcome sight for those on the journey beyond the end of the known world. It meant a reprieve from rancid water, salty meat and ships biscuits filled with weevils. For the soldiers and sailors of the Honorable Company, the promise of a new beginning.

The Voice of Time by Willem Steenkamp

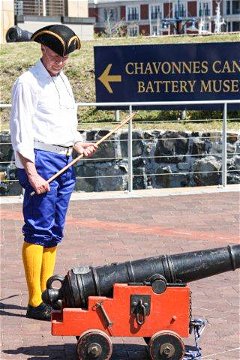

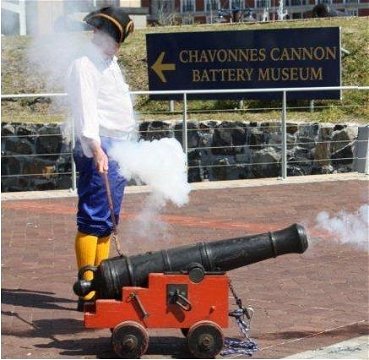

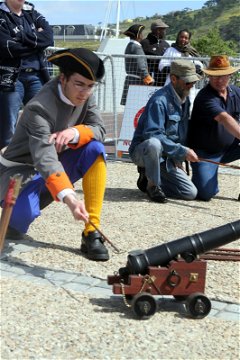

The history of the Noon Gun, chronometers and the Time-Ball Tower. An interesting insight filled with anecdotes and factual information about our Cape Town muzzle loading cannons. A large selection of which is on display at the Chavonnes Battery, some we still fire off regularly.

The daily official V&A Waterfront Historical Walking Tour covers some of the 30 Historical Points of interest at the V&A including the Time-Ball Tower, providing a strategic vantage point to watch for the puff of the Noon Gun! Visit at the Chavonnes Battery for guided tours, cannon firing and lots of fun in any weather...See our recent Trip Advisor reviews and BOOK A TOUR.

The Voice of Time by Willem Steenkamp

One advantage of living in the city is that you will never fail to hear, very loudly and clearly, the true voice of Cape Town … which is not the howling of the south-easter, as some might think, but the boom of the Noon Gun from Lion Battery, on what used to be called the Lion’s Rump.

Some visitors laugh at what one once called “the Cape Town twitch” – Capetonians’ habit of automatically checking their watches when the gun makes itself heard. … just as they have been doing for more than 200 years at different times of the day.

What you might not realise, though, is that if your watch is dead on the hour when you hear the gun, it is actually several seconds slow because of the time it takes for the sound to travel to your ears.

The Noon Gun owes its origins to the increasing sophistication of maritime navigational instruments during the 18th Century. Up to then navigation had been anything but a precise science because it required a fairly accurate idea of the ship’s longitude.

This was not really possible till one a ship’s chronometer appeared in the late 18th Century which told navigators the time with acceptable precision. But the early chronometers were not always dead on, and during long voyages tended to gain or lose small amounts of time which would not concern a landsman but could mean the difference between life and death for a seafarer.

The only way for navigators to keep on track was to check the chronometers whenever they could, and sooner or later most major ports acquired resident astronomers who could provide accurate time-readings for the navigators of visiting ships.

Cape Town did not get an astronomical observatory till 1820, but soon after the second British invasion in 1806 the authorities instituted the practice of firing a time-gun daily from the Imhoff Battery, the Castle’s seaward defence work till its demolition around the turn of the 19th Century.

According to Commander Gerry de Vries in his and Jonathan Hall’s seminal book “The Muzzle-Loading Cannon in South Africa”, the Imhoff gun’s time of firing varied over the next few years till it was finally fixed at 1pm.

The construction of the Royal Observatory in 1820 finally provided shipping in Table Bay with the accurate time-signals they needed. The system used was simplicity itself. A little before noon the navigators on the ships anchored in Table Bay would stop their chronometers and set them precisely on the hour. Then they would keep a sharp eye on the Imhoff Battery.

Precisely on the hour the observatory would signal the Imhoff Battery by dropping a time-ball, or, at one stage, firing a flare (some say a bell-mouthed pistol) from its roof. This would be the cue for the Imhoff Battery to fire one of its guns, and as soon as the navigators saw the puff of smoke from the 18-pounder’s three-metre-long barrel they would start their chronometers.

Around 1864 the system was improved upon by the introduction of electrical signals from the observatory which detonated the gun’s charge – the method used to this day - and about three years later the gun’s time-notch was finally shifted to 12 noon, where it has remained ever since.

Not many people realise that the firing of the Noon Gun is part of Cape Town’s living history in more than one sense. The time-guns (there is always a second gun standing by, loaded and ready for action in case of a last-minute mishap) are the very same ones that were used to set the chronometers ticking on board the sailing ships in Table Bay in the first decade of the 19th Century.

When the British conquered the Cape for the second time in 1806 the Imhoff Battery’s armament consisted of Dutch and Swedish 18- and 24-pounder guns, seven cast of bronze and the others of iron. The British re-deployed all the iron cannon in the battery and replaced them with 27 new 18-pounders, known as “Blomefield guns” after their designer, Major-General Sir Thomas Blomefield, Inspector of Artillery at Woolwich Arsenal from 1780 onwards.

All these years later the Blomefield guns are still doing their duty, the oldest smooth-bore muzzle-loading guns in daily use anywhere in the world. And it has been a long stint. A few years ago it was calculated that as of 1 August 2002 the time-guns had been fired 61 760 times, making that daily dull boom from Signal Hill a truly dynamic link between Cape Town’s past and present.

All that has changed in that time is the venue. In 1902 the time-guns moved from central Cape Town to Lion Battery because after most of a century the Mother City had grown to the point where they made uncomfortable bed-fellows, even though the 18-pounders only fired blank charges.

Cape Town was much larger now, and its pivotal role during the just-concluded Second Anglo-Boer war had swollen its population of both residents and transients. As De Vries notes, “the undignified and sometimes painful parting of unsuspecting visitors and their horses when the gun was fired may have contributed to the decision … to move the time-gun up to Lion Battery, where it would rattle less windows and nerves”.

So the time-guns were laboriously transported up to Lion Battery, and on 4 August 1902 the first noon signal was fired from their new home.

The guns themselves could tell some interesting stories. No 85 served from October 1904 till June 1925, and was then retired when its vent or touch-hole was damaged beyond repair. No 388 served from June 1924 to October 1926, then disappeared and was found decades later at a crèche in Somerset West, with no clue as to how it had got there. Gun 35 has been going strong since 1910 and No 36 since January 1948.

Gun 11’s story is the best of all. Proofed at Woolwich in 1793, it served as Noon Gun from December 1941 to December 1944. Thanks to World War II shortages no electrical detonators were available, so it was fired by the simple but dangerous expedient of hitting a percussion-cap with a hammer on receipt of the observatory’s signal!

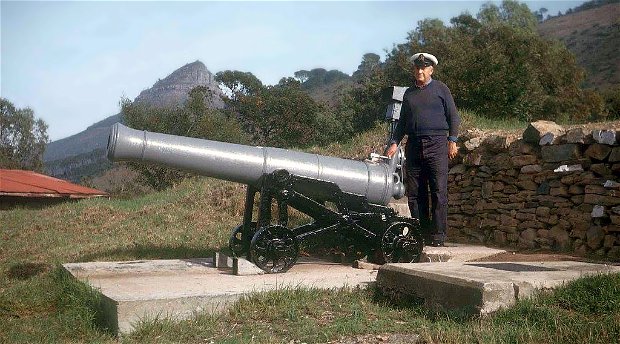

The gun then went out of service and somehow ended up mounted outside Fort Wynyard, near today’s Waterfront, when the fort became a museum of coastal artillery in the 1980s. But when the museum was wound down in 1997 it was rescued and taken back to its old home at Lion Battery.

Noon Gun stories abound, some of them true and others probably not. One tenacious but unproven urban legend from the post-World War II era has it that Lion Battery’s resident cat crawled up the time-gun’s barrel just before midday one day and refused to come out in spite of all the gunners’ cajoling. Then the hour of noon arrived …

Another oldie but baddie which goes back to the 19th Century is the one about the day the gunners allegedly forgot to remove the ramrod from the gun’s barrel after loading it; when the gun fired, the sturdy wooden pole shot out like an arrow, curved gracefully down towards the city and killed a donkey (another version says it was a horse) stone-dead as it stood peacefully in Greenmarket Square. The donkey’s (or horse’s) owner then sued the City council for compensation.

This one is an outright lie, says Gerry de Vries, because among other things “none of the noon guns has ever been aimed in the direction of Greenmarket Square, partly because a wooden rammer would be shattered by the firing, and partly because a broken wooden missile of that shape and sectional density could not travel half that far”. So there.

A Noon Gun story which indubitably true used to be told by that distinguished soldier, Brigadier P F van der Hoven, who as a young lieutenant was in charge of firing the Noon Gun in 1937 and 1938. One day there was a deathly silence at noon, followed by an immediate complaint from the municipality. Van der Hoven made inquiries and was told that the battery mascot, a young baboon, had leapt up on to the breech and stolen the electrical interceptor which was responsible for relaying the current to the gun’s charge.

Van der Hoven found this hard to believe, but next morning he went up to Lion Battery just before noon and stationed himself next to the gun. Sure enough, the malefactor leapt from a tree and straddled the gun, reaching for the interceptor. Van der Hoven thwarted several attempts at theft by rapping the baboon on the fingers with his swagger-stick.

Then it was noon and the gun fired with the baboon still sitting astride the breech, trying to snatch the interceptor tube. As any witness will testify, the Noon Gun produces an awesome amount of noise and smoke when it is fired, and the baboon “gave a mighty scream” and toppled over in a dead faint.

“The gunners came out of their lecture-room, ran and picked up their mascot and threw water over his head. He opened one eye and then the second eye, and then jumped out of the gunner’s arms and (fled) up the hill … He didn’t return to the battery for a week.” And, according to Brigadier Van der Hoven, “he never rode the time-gun again.”

One of the most intriguing Noon Gun stories concerns Gun 54. This gun, according to a letter unearthed years ago by the renowned military historian Commander MacIan Bisset, was moved from the then Castle Ditch in 1923 to replace Gun 17, which had become unserviceable due to an accident while work was being done on its vent.

There it served valiantly for years till … when? All that is known is that at some stage it ended up as one of the two Blomefield’s guarding the Castle’s Lion Gate. Then in 1980 Mr G H Morton, Lion Battery’s commander in the rank of lieutenant in 1945, told Commander Bisset an amazing story.

According to Mr Morton, Gun 54’s barrel-vent was accidentally damaged beyond repair while being refurbished. Being possessed of a guilty conscience, like any junior officer, he decided not to tell his superiors; instead he decided that he would secretly switch Gun 54’s barrel with that of one of the Blomefield outside the Lion Gate. This was duly done at dead of night without anyone being the wiser, he recalled.

True or false? Gerry de Vries is skeptical and thinks the story acquired a few twists and turns in the 35 years between 1945 and 1980. And it is certainly a stretch of the imagination, given that unshipping an 18-pounder’s barrel and replacing it with another is an arduous and highly visible business – and the fact that the Castle then housed a top-secret operations room which ran 24 hours a day in the Kat, where the William Fehr Collection is now located.

On the other hand, desperate men sometimes accomplish unlikely things. And the fact is that Gun 54 stands outside the Lion Gate to this day … and that its inspection report has vanished without trace.

But the myriad stories are a trifling matter to the old guns at Lion Battery. Their ancient task is to mark the arrival of noon, and so they boom away every day under the fascinated gaze of parties of tourists.

Further Reading

The Social and Military Heritage of the Cape is a fascinating saga with heroes and villains of all color and creed. The Chavonnes Battery invites you to discover the strategic Commercial and Military importance of Cape Town and the harbor in global trade and some of the character’s who left a footprint here. Meander among the Archaeology ruins, explore the international photographic exhibitions, join a Guided Walking Tour or fire a real...

Willem tells us about the Round House located in Kloof Neck and some of it's colorful characters.

Share This Post