Testimonials: We would like to express our deepest thanks to all the staff that assisted at the event. They were so patient and friendly and willing to go the extra mile. It was truly an awesome experience and we got such wonderful feedback about your amazing venue.... Living Link On behalf of our entire team, I just wanted to say a HUGE thank you again for hosting our graduation ceremony. It was...

The day the lion blinked by Willem Steenkamp

Lion’s Head played a vital role in the daily business of the Cape in the old days, because the panoramic view from its top made it the ideal place on which to station lookouts who could warn of approaching ships... and then there was the day the lion blinked.

The day the lion blinked - by Willem Steenkamp

The first man to set up a regular lookout system was the hard-driving Governor Isbrand Goske, who took office in 1672. Goske’s main task was to speed up construction work on the Castle, which had been proceeding by fits and starts since 1666, but in 1673 he also gave Lion’s Head an eye of its own by established a signal station on its summit.

This was easier said than done. Whoever lived in those days in vicinity of the vale where Lion’s Hill now stands and went to watch how it was done must have had his mouth hanging open.

Several wagons drawn by spans of wheezing oxen would have battled their way up to the as yet un-named Kloof Nek and then to the foot of Lion’s Head, laden with items which included kegs of gunpowder, food supplies, various large flags, a powerful telescope and two bronze breech-loading guns with their swabs, rammers and linstocks. Possibly the load included a tall flagpole, although this might have been made on the spot from one of the many trees on the slopes.

That was the easy part, however. Everything had still to be hauled up the near-vertical sides of Lion’s Head by dint of hard labour and, no doubt, much bad language, but hauled up it was, because Governor Goske was a man who insisted on getting his own way.

A hut was built on the Nek, which became known as “Vlaggemans Kloof”, for the signallers who took turns manning the lookout post during the daylight hours. Their duties were simple but important. When they sighted a sail they were to hoist the flag and warn the Castle by firing one shot for each vessel. Then, when the ships were near enough for the signallers to make out their ensigns, they would hoist an identical one to inform the Governor about who was coming to visit.

Since the signallers could spot ships out to about 48 kilometres on a clear day, this gave the Castle plenty of time to prepare. The great guns on its battlements would be made ready either to fire round shot at invaders or blank charges in a salute, whichever was appropriate; a guard of honour would be assembled in case some high dignitary was on board, while shopkeepers and near-by farmers would prepare to sell their merchandise to the visitors.

Most importantly, a boat would be made ready to meet the newcomers in Table Bay, one of its occupants being a surgeon who would check to see whether any of the ships had a contagious disease on board. This was a vitally important precaution in an era which predated vaccines or antibiotics, and the return-fleets heading for Europe were particularly dangerous because the East was rife with deadly diseases.

Lookout duty must have been a pleasant task in some ways because the “flagmen” were free of the perennial grind at the Castle, where each strictly regulated day started early and ended late, with hawk-eyed non-commissioned officers ever on hand. On the other hand, it was anything but a picnic.

In the dark small hours of every morning one of the signallers would roll out of bed in Vlaggeman’s Kloof and climb to the foot of Lion’s Head, laden with food, water (and probably something a little stronger to keep the cold out), warm clothing and such extras as fresh gunpowder for the two breech-loaders.

If he had timed it right, he would reach the steepest part of the climb at first light, so that he could see what he was doing as he hauled himself up with the aid of a thick rope whose other end was knotted around the base of the flagpole. Then he would spend the rest of the day on the summit; near last light, while it was still possible to see where he was going, he would come down again.

If all went well, that is. Commander Gerry de Vries writes that “there were occasions when the weather changed for the worse too rapidly for the lookout to return to base, and he had to spend a miserable night or two on the mountain”. Small wonder that eventually a shelter was built for the lookouts on the summit, as well as a waterproof magazine for the gun-powder. It was a good system, but vulnerable to human error like any other, as was most horribly proved in 1713.

A return-fleet arrived from the East Indies with an outbreak of smallpox on board. But the flagman on duty, so the story goes, was drunk that day, and he failed to notify the Castle that the fleet was approaching. The fleet anchored in Table Bay without being inspected, and before long a smallpox epidemic was raging on shore.

It is surprising that this had not happened at the Cape up to then, since ships had been calling there for two centuries, but now the time had come, and it was a catastrophe.

The horror of a 17th-Century smallpox epidemic is almost inconceivable to a modern person. Swift, virulent and highly infectious, it had spread from Egypt to Europe, China, India, Africa, and the Americas, and was one of the greatest killer diseases known to mankind; the warlike Inca empire, some believe, would not have fallen to a handful of Spanish soldiers in the 16th Century if it had not first been fatally weakened by smallpox.

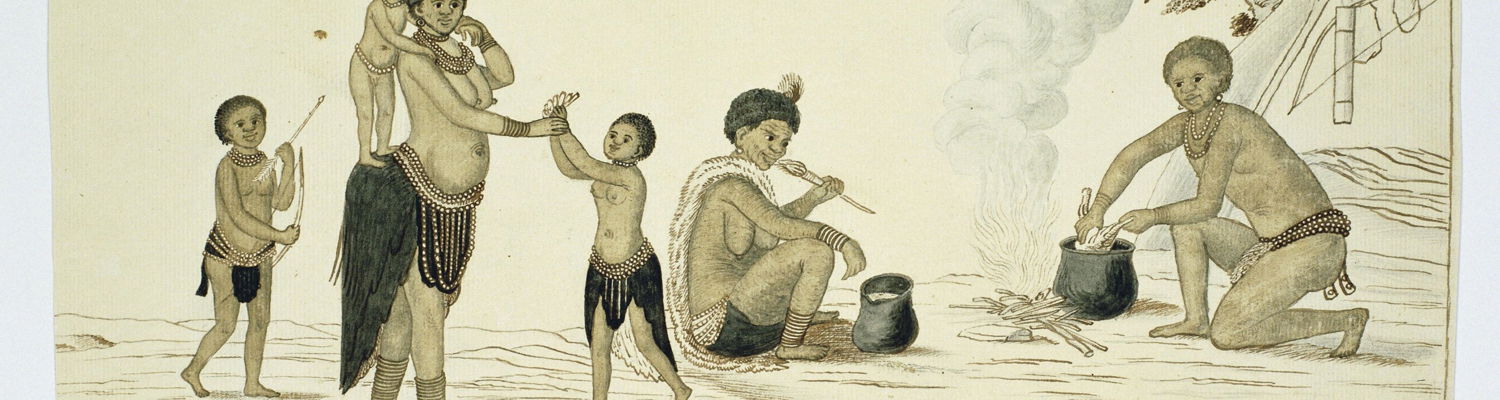

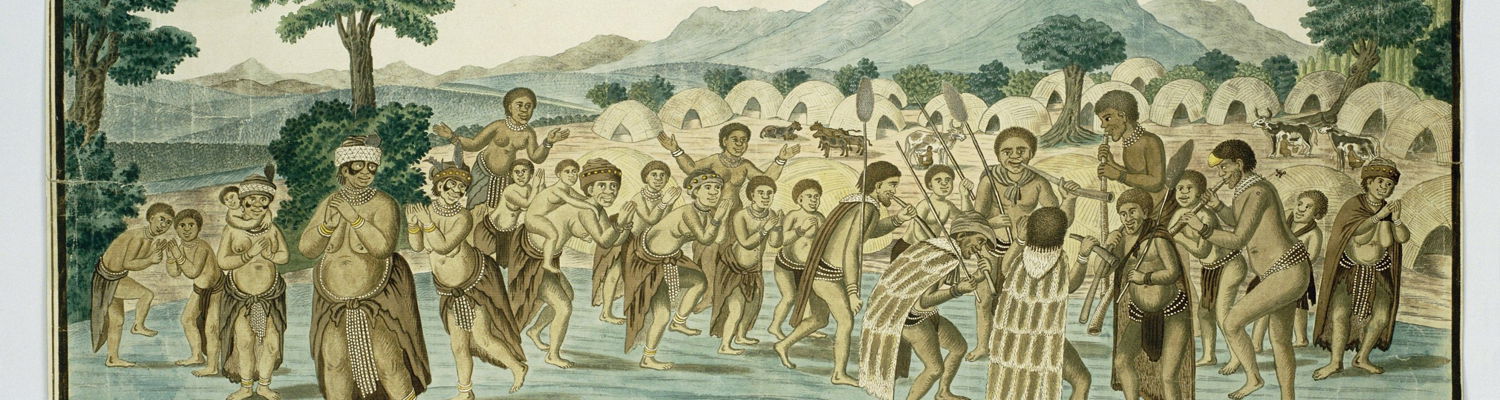

The small Cape settlement suffered grievously, but the greatest devastation was visited on the Khoi population trading with or working for the VOC. Completely non-resistant to the disease, the Khoi succumbed in great numbers, and fleeing survivors took it inland with them. The result was a great dying before the epidemic burnt itself out.

The epidemic was a death-blow for the Cape’s traditional Khoi society. Inherently fragile because it consisted of a loose network of pastoral clans, it had been steadily breaking down for years, not through being crushed by the Dutch but because of a combination of factors which included the continual bartering of cattle or labour for European goods:

According to the authoritative academic Professor Richard Elphick, a Khoi who “sold his heifer to a Dutch bartering expedition, or his labour to a colonist … was exploiting the colonial situation for his own ends; but, though he did not know it, his immediate interests were incompatible with the continuing autonomy of his traditional society.

“These seemingly minor actions, and the processes to which in aggregate they gave rise, are less often witnessed by our documents than the episodes of conquest. Nonetheless, they were the fundamental determinants of Khoi-Khoi decline".

So the smallpox struck the Khoi at their moment of greatest weakness. Exactly how many died will never be known, but Elphick estimates that something like nine-tenths of the Khoi population in the VOC-influenced area and beyond had perished by 1715.

The Khoi came so close to total extinction, in fact, that according to the historian John Laband the DEIC’s small population of officials, free burghers, free workers and slaves actually outnumbered the remaining clan’s people by the end of the 18th Century. It was a vast demographic shift which drastically altered the Cape’s – and South Africa’s - future.

And it all started because on one particular day the Lion blinked. Debauchery has caused many disasters in the history of the world, but surely few as vast as this.

The lookout system stayed on as the century got older, evolving all the time. In 1741, for example, a second signal post was established on the Lion’s Rump to relay signals when a south-easter was blowing or Lion’s Head was shrouded by fog.

By the 1780s pairs of flagmen spent eight days at a time in the cottage at Vlaggemans Kloof, taking turns on Lion’s Head itself and received the same pay, rations and cash food allowance as skilled men like ships’ quartermasters.

Thanks to instability in Europe this was a time of especial danger to the DEIC, which, like its English and French opposite numbers, was closely allied to its national government. Thus the flag the signallers hoisted on sighting ships was of a certain colour which changed every year, so that captains returning from Batavia could check their written instructions to see whether the DEIC still controlled the Cape.

The DEIC’s lookouts on Lion’s Head and the Lion’s Rump served up to the first British invasion of 1795. Their successors of the Batavian Republic, to whom the Cape was handed back in terms of the 1802 Treaty of Amiens, witnessed a historic sight on the morning of 4 January 1806: the arrival of a massive fleet of almost 60 British warships, troopships and transports under Admiral Sir Home Popham.

The British ships rolled and pitched for two days in the grip of a monumental south-easter while the Cape’s chain of signal guns alerted outlying soldiers and Lieutenant-General Jan Willem Janssens feverishly organised his scanty military forces. Then the wind dropped enough for the Popham to start landing his troops and guns, and on 8 January the British victory at the Battle of Blaauwberg left the Cape firmly in British hands.

The institution of a regular mail service between the Cape and England in 1815 was the beginning of the end for the Lion’s Head lookout post, and in 1821 a permanent signalling station was erected on the Lion’s Rump, which had been re-named “Signal Hill”. This was less of a hardship post than the one on Lion’s Head, but it was no sinecure either.

Everything the signalmen and their families needed had to be dragged up by way of a tortuous track cut out of the rock and bush of the slope.

And so, after almost 150 years, the great stone lion’s vigilant eye closed forever. The flagmen’s square stone cottage survived for another half-century or so, however. At first it served as a convict station, but by the 1850's it had become a small hostelry known as the Strangers’ Inn.

Some time in the 1870s it vanished, although the Kloof Temperance Hotel was still functioning on the same spot in the 1890s, its proprietor being one Jas T Higgo, whose address was given as Upper Kloof Road, in the area now known as Higgovale. Two more generations of Higgos were to run the hotel.

All traces of those flagmen have vanished. But next time you drive over the Nek from Lion’s Hill to Camps Bay and pass the spot where the flagmen’s little stone cottage once stood, drink a mental toast to those hardy, weather-beaten and occasionally drunken fellows who were the Lion’s eye for so many long years.

Willem Steenkamp, historian, storyteller and author is the curator of the Chavonnes Battery. For these and many more stories of the early history of the Cape, visit the Chavonnes Battery. Book a Tour

Further Reading

Thousands of visitors to the V&A Waterfront have seen the huge Cannons mounted on immense gun-carriages on the Ramparts and at the entrance of the Chavonnes Battery Museum, but hitherto few have known anything about their history. These seven cannons are part of the largest selection of Muzzle Loading Cannons and inside the Museum are fascinating models and detailed displays and exhibits and Cannons that still fire a shot of black power.

It is with great sadness we mourn the passing of our beloved colleague Sinovuyo Nogaga who tragically died when he was hit by a train on his way to work Saturday morning. Our sincere condolences to his loved ones, his family, our team, his friends and the industry. We are heartbroken at the loss of our Vuyo, a born free with a bright future cut short. Having access to safe transport to...

Share This Post