Circle of Saints - Macassar

Willem Steenkamp shares an insight into the history of Islam at the Cape and the significance of Macassar

"Stories for Freedom: Re-imagining Macassar Township" is an initiative by Proudly Macassar Pottery to host a day of storytelling in Macassar township to help community members tell and record their stories. CLICK HERE to support this project.

The Chain of Safety by Willem Steenkamp

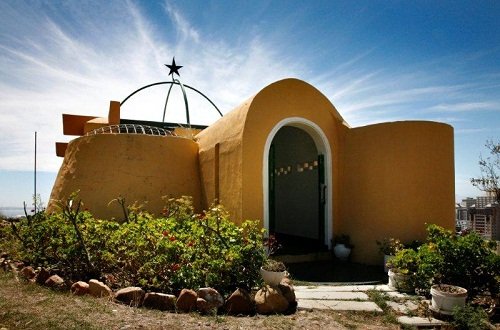

If you are a resident of Lion’s Hill, any Muslim will tell you that are fortunate indeed, because you live in the very shadow of a beautiful little kramat or shrine, easily visible on the left of the road along the Lion’s Rump to Signal Hill, in which lie the bones of Sheikh Mohamed Hassen Ghaibie Shak al Qadri, an “Alliyah”, or Friend of Allah.

Not only that, but the kramat is an essential link in a holy chain which, by ancient tradition, protects the entire Cape Peninsula from famine or plague. Who could possibly ask for more than that?

Muslims started arriving from India and today’s Indonesia in the early years of the little victualling and ship-repair outpost which later became known as Cape Town. Some were slaves, while others came of their own volition and followed various occupations and trades, and yet others were exiled here for greater or lesser periods.

As a result the Cape Muslims were able to retain and maintain the essential elements of their religion and culture, while other groups of incomers who arrived as solely as slaves – Guineans, Angolans, Madagascans, Mozambicans and a great many Indians – entered the religious and cultural mainstream of Cape society within one or two generations.

Not everyone realizes that “Slams”, a common colloquial Afrikaans term for the descendants of those early arrivals from Indonesia, is actually a corruption of “Islam”.

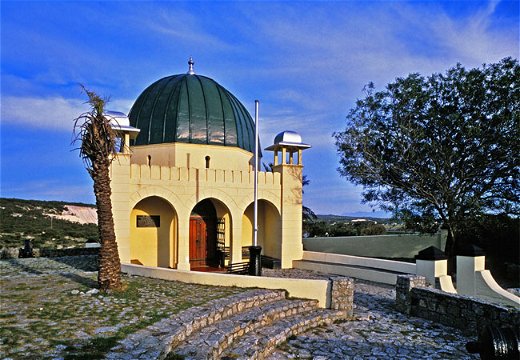

Sheikh Mohamed’s story is intertwined with that of the exiled Sheikh Yusuf of Macassar, a deeply learned man and the most famous figure in Cape Muslim history – a man who “was not only of noble birth but of unusual piety, a great warrior, a great prince and also a priest deep in the knowledge of holy things,” as the historian Ian D Colvin wrote.

Near the end of the 17th Century Sheikh Yusuf was living at Banten in western Java, where he was the chief religious judge and personal advisor to the ruler, Sultan Ageng, who was also his father-in-law. In 1680 Sultan Ageng’s son, Pangeran Hajji, rose against his father. Sultan Ageng rallied and in 1683 besieged Pangeran Hajji’s fortress.

Pangeran Hajji got himself out of this tight spot by asking for – and receiving -Dutch military aid, and eventually Sultan Ageng was defeated and the 57-year-old Sheikh Yusuf was made prisoner.

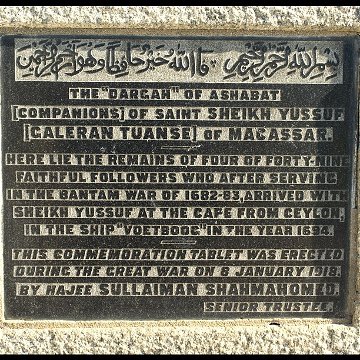

Initially he was held at Ceylon, but was a man of such influence that it was decided to exile him to a place remote from the East Indies. He arrived here in 1694 on the ship Voetboog, accompanied by Sheikh Mohamed and 48 other followers, wives and children.

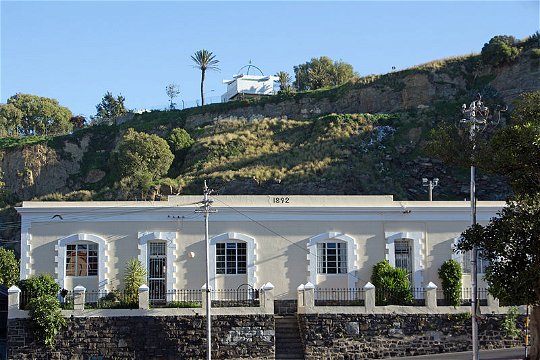

The Dutch East India Company spent considerable sums to maintain Sheikh Yusuf and his entourage in some state at its farm Zandvliet, which was well away from Cape Town. The idea was to minimize any influence he might exert on the local Muslim slaves and free men, but the stratagem failed.

The practice of Islam was tolerated at the Cape, but its adherents lacked spiritual guidance. Sheik Yusuf filled that gap till he died in 1699 and was interred near by. His followers were given the option of staying on at the Cape or returning to Banten. Most of them went home, but his daughter and two very learned teachers who had been among his most devoted protégés elected to stay behind to continue ministering to the Cape community.

One of them was Sheik Mohamed; the other was Tuan (“Mister”) Kaape-ti-Low, who is buried in a much smaller kramat further along Signal Hill, near the scout camp.

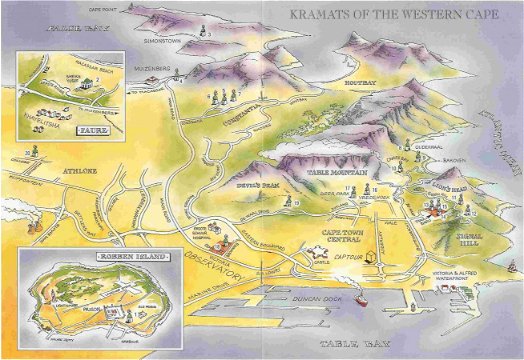

Cape Muslims like to relate that more than 250 years ago it was prophesied that one day there would be “a circle of Islam” around the Cape which would protect it from harm; and in due course this came to pass.

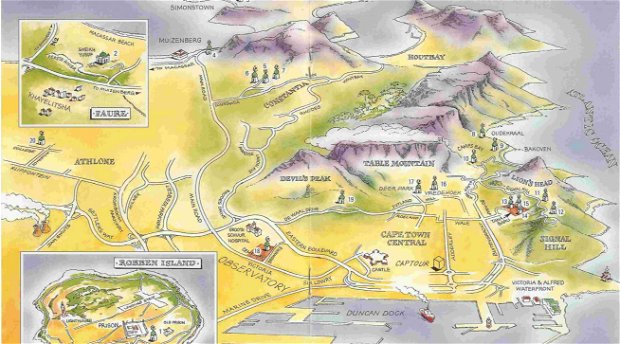

The circle starts at the Tana Baru, the old Muslim cemetery at the top of Strand Street just above the quarry, goes up to the kramats on Signal Hill, and then carries on to Oudekraal, Constantia, Macassar and Robben Island.

The most notable of them is empty, because Sheikh Yusuf’s remains were later re-interred at Macassar (today’s Ujung Pandang), but its spiritual force is as strong as if the hero of Banten still rested within its walls, and the Zandvliet area was renamed “Macassar” many years ago in honor of the holy man’s place of birth.

Non-Muslims do not always realize what sacred ground a kramat is. For Muslims, visiting Sheikh Mohammed’s kramat or any other is not a casual spur-of-the-moment thing. They are expected to arrive purged of profane thoughts, and to recite from the Quran and pray.

So if Lion’s Hill residents visit Sheikh Mohammed’s kramat they should remember to observe some small decencies. They should remove their shoes when entering, and should not sit on the actual grave, put their feet on it or lean on it; and they should avoid loud conversations and refrain from such worldly indulgences as smoking.

The name of the game is “respect”, the very oil of civilization. That is surely what Sheikh Mohamed and Sheikh Yusuf would have wanted.

For more information on the cover picture, Click Here

Share This Post