Fools Gold by Willem Steenkamp

All about the Lions Head Gold Mining Company (Cape Town) 1887 and other foolish pursuits for the land of Monomotapa. Visit the Chavonnes Battery, Clock Tower, V&A for fascinating insights into the history of Cape Town.

FOOL’S GOLD AT THE LION’S FEET by Willem Steenkamp

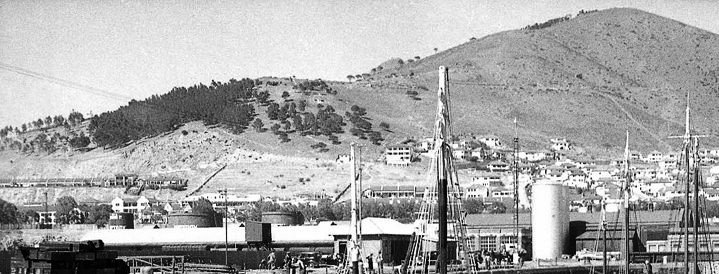

It would be difficult to visualise it now, but the restful slopes of Lion’s Head on which Lion’s Hill now stands once resounded to the clink of pick and shovel as a horde of hopeful Capetonians staged a genuine gold rush … such as it was.

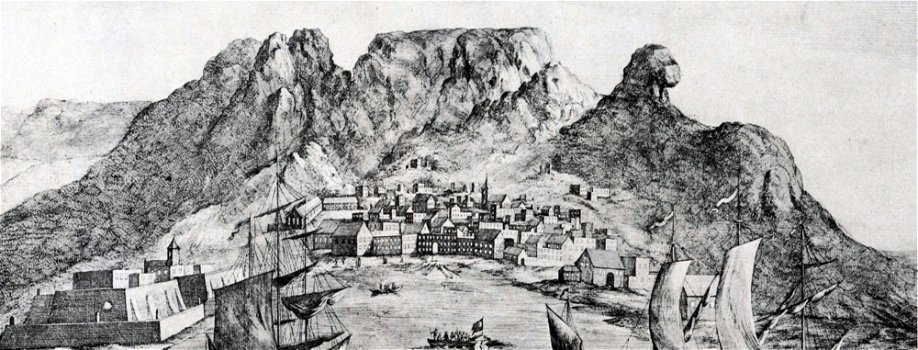

Stories of hopeful prospectors hoping to strike it rich on the slopes of Lion’s Head or its environs go back almost to the birth of the Mother City. The search for precious metals started as early as 1654, when the Cape outpost consisted of little more than the cramped clay-walled “Fort de Goede Hoop” and the fruit and vegetable gardens.

No doubt this was partly due to the firm belief, held by Jan van Riebeeck and several of his successors, that somewhere in Southern Africa’s completely unknown interior there existed a fabulous African empire called Monomotapa, in which gold was said to be as common as lead.

The Dutch East India Company being strictly a commercial operation, the discovery of gold or silver would have added great value to the Cape outpost. The Cape itself had cost and was costing large sums which were regarded as a necessary investment because of the need to supply fresh food and ship-repair facilities for travellers to and from the Far East, but it could not pay for itself.

Alas, Monomotapa did not exist. There was gold to be had, but only far inland, and the tribes who mined it were well aware of its value, although two centuries would pass before the later Witwatersrand yielded up its riches … although, strangely enough, Van Riebeeck’s examination of the all the available “evidence” indicated that Monomotapa’s alleged capital city, Davagul, was located in the later Johannesburg-Pretoria area.

Pure co-incidence, or the result of secret knowledge that was subsequently lost? No-one will ever know, and it is likely to remain one of those great South African mysteries.

And so there was great excitement in 1654, when a soldier of the garrison who described himself as a former silversmith claimed to have found a lode of silver near today’s Kloof Nek. Sadly for all concerned, however, the silver – if, in fact, it was silver - proved so scanty and difficult to dig out that, as the commentator Gijsbert Heeck later wrote, “it could not cover the costs and for that reason was not further developed”.

The VOC did not give up, however. In 1687, under Simon van der Stel’s governorship, shafts were dug on the Steenberg, but this also proved fruitless, although the place-name “Silvermine” and the old prospecting shaft remain to remind us of those early blasted hopes.

Gold remained the main attraction, though, and it would appear that the VOC continued to persevere. In 1676 Jan van Riebeeck’s son Abraham stayed over at the Cape for about a month while travelling out to the Far East as a newly appointed “assistant merchant” (this title was used for everything from an actual merchant to an official), and mentioned in his diary that he went out to “inspect the mines behind the head of the Lion Hill, the Upper Merchant finding there some good stones”.

But these efforts, too, were doomed. In a book published 12 years later, Pére Tachard, one of six Jesuit priests who called in at the Cape while on a mission to the King of Siam, commented that “some affirm that there are gold mines at the Cape. They showed us stones found there which seemed to confirm that opinion: for they are ponderous, and with a microscope one may discover on all sides small particles that look like gold”.

Interest in possible gold-bearing ores was not confined to the Kloof Nek area. In January 1825 there was some discussion of ore samples found during the making of a road between Sea Point and Camps Bay, but when samples were analysed it was concluded that “they had very much the appearance of being interspersed with golden specks; but on examination they proved to be nothing but mica”.

More than three decades later, in 1859, a certain Captain Glendinning caused a brief stir when he claimed that he had found gold on his property, but hard reality soon pricked that bubble as well.

It was a different matter altogether in 1886, when Capetonians brushed aside the fact of more than 200 years’ worth of failed attempts and launched themselves into the sort of frenzied gold-rush which had taken place along the Witwatersrand.

The hastily-formed Lion’s Head Gold Syndicate dug several shafts on what seemed a promising site on a farm on the slopes of Lion's Head, and amid great expectation rock samples were taken to Wilkinson’s Mill in Kloof Street to be pulverised and assayed. Small quantities of gold were extracted, but the project quickly proved to be uneconomical.

In 1887 Dr P D Hahn, Jameson Professor of Chemistry at the South African College, a famous character of his time who was known far and wide as “the Klip Doctor”, took samples of his own at the site, and in a report dated 4 May of that year claimed that 39½ grains of gold had been extracted from an 80-pound rock sample

Dr Hahn opined that “the contact-zone between granite and slate from Sea Point to the neck between Devil's Peak and Table Mountain is auriferous, and … gold will be found everywhere in this zone".

That was enough to send scores of gold-crazy locals swarming up the slopes, no doubt reassured, like the good smug Capetonians that they were that the Almighty would not strew His largesse over the barbarous Transvaal and ignore God’s own country on the southern side of the Hex River.

Not all Capetonians succumbed to the craze, however, and cooler heads evidently began to worry about their beloved mountain being turned into a claim-pocked wasteland. One Mr Thomas Roberts asked that Dr Hahn be kind enough to indicate the extent of the gold-bearing zone to give prospectors some guidance and "thereby save the Lion from having his poor old hide scratched all over its surface".

In the meantime the Lion's Head Gold Syndicate carried on prospecting. By the end of the year, after 18 months of hard work, it had sunk a shaft 145 feet deep which had yielded results encouraging enough for the formation of the Lion's Head (Cape Town) Gold Mining Company to be advertised in December 1887.

A local analyst declared that the quartz from Lion's Head contained a small amount of gold – “one pennyweight to the ton, or something like it", as a contemporary account put it – but the syndicate wanted the assurance of a totally independent firm of analysts, so several tons of quartz were carefully sealed in bags by a government official and sent off to Germany for assaying.

The sealing up of the quartz was carried out in ceremonious occasion, champagne corks popping all round, but there wasn’t much to celebrate when the results came back and stated that “there was not an atom of anything resembling the precious metal in the whole of the quartz”, according to an account of the time, “and …it was only so much common rock which had not paid the cost of its shipment".

That burst the bubble in no uncertain terms, and the syndicate was liquidated. The last doleful act in the gold-rush drama that wasn’t came in 1891, when the Cape Town Public Works Committee instructed the Gold Syndicate to fill in the Lion’s Head shaft or fence it off, on the grounds that it was a source of danger to passers-by.

Another shaft, dug on the Sea Point flank at the same time, likewise failed to produce anything worthwhile, although it managed to kill someone when a prospector called Jacobus Vlok of Kloof Street fell down it and suffered mortal head injuries.

In 1951 a fire-fighter narrowly escaped the same fate as the unfortunate Mr Vlok, and the shaft was filled in with such thoroughness that all knowledge of its location was lost. Mona de Beer, author of that marvellous book “The Lion Mountain”, wrote in 1987: “I have searched the slopes above Fresnaye, around the neck between Lion’s Head and Signal Hill, but have never found remains of the shaft, so good luck if you seek to verify this!”

There was to be one more bit of excitement for treasure-seekers at the beginning of the 20th Century, when loads of Kimberley’s famed “blue ground” was brought in during the construction of a golf course near the Glen. But a local geologist soon deflated all hopes by inspecting the “Kimberley gravel" and reporting that all it consisted of was … well … gravel.

The irony of this feverish pursuit of mineral riches was that there was treasure to be found everywhere on the slopes of Lion’s Head; it was just that nobody recognised it.

All around those gold-seekers in the earlies – literally under their feet, in fact - was one of the handful of great floral kingdoms of the world, a unique natural asset which was to become famous throughout the world.

CLICK HERE for more info

Share This Post